A Trial Lawyer

INTRODUCTION

Walking into my office you will see a framed playbill of the September 3, 2003 fight between Oscar de la Hoya and Shane Mosley aptly titled “Redemption”. De la Hoya lost to Mosley in a split decision in 2000 and this was the fight that could bring redemption. After a 12-round bout with no knockdowns, Mosley was awarded a controversial unanimous decision that is still argued about in boxing circles. The playbill reminds me that even the greats lose from time to time, so remain humble. It also reminds me of the great Mike Tyson quote, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Some lawyers fear the courthouse due to insecurity, bashfulness and lack of confidence: They should read this. If you didn’t finish at the top of your law school class: You should read this. If you did finish at the top of your law school class: You should read this. If you are not a lawyer but looking for a story of confidence, perseverance, and persistence honed through trial and error, you too should read this.

If you don’t have a mentor, read this and email me with questions (jmorris@jamlawyers.com). I am committed to helping you avoid my mistakes and become the best trial lawyer you can. These are practical real-life examples of what lies beyond the bar. Education begins upon graduation and most of what matters is learned through trial and error. Nothing here is intended to take away from the incredibly important work of briefing, appellate, and case management lawyers. They are indispensable. As a sole practitioner, we wear all of those hats.

I’ve lived the John Grisham novel, packed with the treachery, insults, surprises, failures and successes endemic to the practice of law. I too am a work in progress, and I have no idea how this story will end. I show up every day hoping that a person with a righteous cause will knock on my door or send me an email. You should too.

This compilation of case stories and experiences details successes and failures I’ve had along the way. I’ve suffered embarrassment, failure, and disrespect along the way. I’ve experienced success, recognition and respect as well. Occasionally, loneliness and doubt have crept into my mind. The most important factor in my longevity is persistence. Through it all, I’ve shown up, suited up and focused. There is a path forward. The power is within you.

Persistence

“Nothing in the world can take the place of Persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and Determination alone are omnipotent. The slogan “Press On” has solved and will always solve the problems of the human race.” Calvin Coolidge

Deborah Hayes v. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2004)

Fen-Phen was a diet drug manufactured by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. For many patients it worked. For many, it caused heart valve damage, and for some, a deadly condition called primary pulmonary hypertension (PPH). The first round of Fen-Phen litigation in the late 1990’s was wildly successful as Texas plaintiff’s lawyers Kip Petroff, George Fleming, Kathy Snapka and others won state court verdicts while the lawyers in the Federal Multi-District Litigation in Pennsylvania exposed the known dangers of the drug and the manufacturer’s failure to warn. The jury verdicts helped push a nationwide settlement of thousands of cases and a court approved second wave process for litigation of opt-out claims. The “opt-out plaintiffs” could pursue their claims without punitive damages and in turn would not receive the six thousand dollars being offered under the national settlement agreement.

I handled Provost Umphrey’s first wave of Fen-Phen cases and remained in charge of our opt-out clients. To me, no client should take the six-thousand-dollar settlement since the signature injury was heart valve damage. Despite Wyeth’s assertion that most valve injuries were minor medically, we believed juries would offer more in compensation. After all, what matters more than the heart?

The American civil justice system is critical in balancing the rights of the individual with those of the corporations. The uncertainty of jury verdicts creates the tension that allows David to take on Goliath. Without uncertainty and the legitimate risk that Goliath gets harmed by a well-placed stone, Goliath would stomp on David at every turn. Jury trials create the leverage that keeps citizens and corporations honest. Trials are a regulatory tool more effective than legislation. As Jefferson famously said, “the jury trial is more important than the right to vote”.

Following the first wave of settlement, I confirmed with my senior partner Walter Umphrey, that we would move forward on the opt out cases towards trial and he agreed. As with any case, we provided the plaintiffs for depositions, developed the medical evidence and prepared the cases for trial. My first trial setting occurred in Jefferson County, Texas before the honorable Gary Sanderson. My client was a lovely woman from east Texas named Deborah Hayes. Deborah had taken the drug for weight loss and developed mild aortic regurgitation as well as moderate mitral valve regurgitation. I hired Dr. Al Brady, a local cardiologist, as our expert witness to explain the workings of the heart to the jury. We also retained Dr. Lemuel Moye’, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Medical Center as an expert to explain the medical research implicating the drug as a cause of heart valve damage and what was known by experts in the field, including Wyeth.

A week before trial, I received a phone call from a prominent Houston plaintiff’s lawyer who had thousands of Fen-Phen cases. He was a close friend and colleague of Mr. Umphrey and an accomplished trial lawyer in his own right. The conversation went like this:

Houston Lawyer: Jim, we understand that you are about to try the first fen-Phen opt out case in Judge Sanderson’s Court. Is that correct?

Me: Yes, we pick a jury next Monday.

Houston Lawyer: Jim, we’re concerned because if you go down there and fuck it up, it impacts all of us.

Me: I don’t think that I’m going to fuck it up.

Houston Lawyer: We have some options for you. I’m sure Judge Sanderson would consider continuing the case to a later date and we could send a team over to try the case for you.

Me: I’ve prepared the case and feel comfortable trying it on my own.

Houston Lawyer: I can call Walter and discuss the options with him:

Me: Well, let me speak to him first and I’ll call you back.

What I didn’t know at the time was that a room full of other plaintiff’s lawyers with fen-Phen cases were in the Houston conference room of this lawyer listening to our discussion. I made an immediate bee line to Umphrey’s office to discuss the conversation. Our conversation went like this:

Me: Chief, I just got a phone call from a Houston lawyer who wants me to continue the Fen-Phen case I have set next week and allow his team to come over and try it.

Umphrey: Are you ready for trial?

Me: Yes

Umphrey: Have you taken all the depositions you need and hired experts?

Me: Yes

Umphrey: Call him back and tell him to go fuck himself, he said with a chuckle.

I called the Houston lawyer back and explained that we would move forward on our own without quoting Umphrey to which he replied, “Okey Dokey”.

Walter Umphrey was from the old school of trial lawyers and maybe the original school. He graduated from Baylor Law School which now is named the Sheila and Walter Umphrey Law School in 1965. Since the early 1970’s, Umphrey relied on personal injury trial practice to build his firm and his fortune. He was a pioneer in asbestos cases leveraging his union connections at the local refineries to represent thousands of union workers with asbestos related illnesses.

Umphrey was intimidating both in size and comportment. His primary strength was his disarming presence. On numerous occasions, I watched colleagues succumb to his wishes for no good reason other than being intimidated. He did not have one insecure bone in his body. He expected his lawyers to try cases. Having no fear of the courtroom was essential to success at Provost Umphrey. All lawyers were evaluated by their willingness to take a verdict. If you feared the courtroom, you needed to work elsewhere. To Umphrey’s credit, he was less concerned about the result than he was about your commitment to trying cases. Regardless of his success as a businessman outside of law, Umphrey only identified himself as a trial lawyer. Everything else was secondary to that identity. Anytime he received an unknown phone call, he would refer to himself as a trial lawyer in Beaumont.

By 2004, I had worked for the firm for 16 years. I knew what Umphrey expected and I was prepared to deliver. Despite the lack of confidence from the Houston contingent, knowing Umphrey supported my efforts allowed me to ignore what at a younger age would have been disturbing. Trial is competition and confidence is critical to success. Juries can sense whether you believe in the cause. Your self-belief bleeds over in your presentation.

Wyeth was defended by Arnold and Porter, a huge Washington D.C. firm that represented them nationally and local law firm Germer Gertz whose partner Paul Gertz took the laboring oar. At trial, Wyeth brought in Vinson and Elkins partner Bill Sims from Dallas to lead the trial team, so the courtroom was packed primarily with the defense team.

Trial began the following week. Our jury foreperson was a local schoolteacher. The evidence came in predictably and no real surprises occurred at trial. The jury paid rapt attention to both of our experts as we focused on the Wyeth supported studies whose “loss to follow up” participants were not included in the studies. Including those participants would have greatly impacted the results of the studies and given a clearer picture of the predictable risks posed by the drug.

The trial lasted a week and a half and was attended by many plaintiff’s lawyers curious to see whether the case had legs. We argued the case late on a Wednesday afternoon and I suggested that a fair verdict would be four hundred thousand dollars given my client’s young age and unknown medical future. Wyeth, of course, argued that no award should occur because they had done nothing wrong, despite their complete failure to warn of heart valve damage.

The jury retired to deliberate. They went home that evening without reaching a verdict. The next morning, I opened our local newspaper, The Beaumont Enterprise, and was shocked to see a full-page advertisement from the American Tort Reform Association labeling Beaumont, Texas as a “Judicial Hellhole”. Coincidence, I think not. Unfortunately, tying this advertisement to Wyeth wasn’t something we could do before the jury continued their deliberations.

When I arrived at court that morning, I immediately asked for a brief hearing to discuss the Ad with the court. Judge Sanderson had also seen the Ad and understood how it might impact the jury. I asked him to poll the jury to determine whether any jurors had seen the Ad. Fortunately, all jurors denied seeing the Ad and we decided to let deliberations continue without moving for a mistrial.

During deliberations, I was approached by a Houston lawyer named Mike Leebron. He told me that he was present at the Houston lawyer’s conference room when the phone call was made before trial. He said that he sat through the trial and reported back to the group by email. He thought the case had gone well and promised to send me the reviews, some good and some critical, that he had sent to them. I thanked him and continued to wait for the verdict. A few hours later, the bell rang, and the jury entered the packed courtroom to announce their verdict.

The jury unanimously found for Mrs. Hayes and awarded her $1,400,000.00 in the first opt-out case in the country. All lawyers were ashen for different reasons. I was interviewed in the hallway by the local news media and the case was reported the next morning in the Wall Street Journal. Whew. I returned to the office and went straight to Umphrey’s office to deliver the good news. He called the Houston lawyer and gave him the needle over the remarkable verdict.

After our success in Hayes, I began working up cases for trial in Philadelphia, PA with Kip Petroff. Kip is a legend in Fen-Phen circles given his first and most significant trial in Marshall, Texas during the first wave of cases. He recovered over $20 million and put the litigation on the map. Our first case in Philadelphia was a two-case consolidation tried along with fellow plaintiff’s lawyers Mike Miller and Ed Williamson. Our client Hank Klepper, was an extremely likeable early 40’s auto shop owner from Katy, Texas who was otherwise completely healthy. He had moderate mitral valve regurgitation, but no actual symptoms. Had Hank remained in the settlement, he too, would have only received six thousand dollars. His was the kind of case I thought had a value of fifty thousand dollars. We kept in mind that a reasonable global settlement value was the goal. As I told anyone who would listen, the cases should settle globally for fifty grand a piece. We tried Klepper under the same evidentiary limitations as Hayes disallowing punitive damages, but the Judge required reverse bifurcation meaning that we would try damages before liability. This made securing a large verdict very difficult since the jury had nothing to get angry about.

Ed Williamson, a tall late 60ish Mississippi attorney, was colorful to say the least. In voir dire, he told the jury in his southern drawl, “Ladies and Gentlemen, I too, am from Philadelphia… Philadelphia, Mississippi.” An objectively funny line, it fell flat. The jury remained stone faced. The trial went about as we expected. The jury deliberated the case and did not find in favor of Ed and Mike’s client but did find for Mr. Klepper and awarded him fifty thousand dollars, exactly what I had argued for.

Before beginning the second phase and presentation of liability evidence, the judge mediated the damages verdict to avoid the time and expense of the next phase. Wyeth wanted to pay half the amount and I wasn’t having any of it. I told the Judge that we had been reasonable in our request to the jury, and fifty grand was nothing for Wyeth to pay. To his credit, the judge got it and told me, “sometimes it is important to save face.” Sure enough, the judge convinced them to pay and we were off to our next trial.

Kip and I tried two more consolidations successfully in Philadelphia and were helped significantly by a $200 million verdict generated by Steve Kherkher and John Boundas of Houston powerhouse Williams & Bailey. Ultimately, all of the cases settled and the litigation ended. My last real involvement in Fen-Phen was as Philadelphia local counsel for John O’Quinn who had secured his own enormous Fen-Phen verdicts in Texas with Partners Tom Pirtle and Rick Laminack, two extraordinary trial lawyers. O’Quinn co-counseled with Provost Umphrey in the Texas tobacco case that I too worked on. He was a legendary a trial lawyer. A book should be written about him, though I’m not sure people would believe it. O’Quinn was beset with demons that somehow did not interfere with his success. I recall seeing him in vulgar fashion verbally dismantle young partner Kendall Montgomery in the lobby of the Texarkana Holiday Inn following a mock trial in the tobacco case. Had Montgomery punched him in the face, no one would have objected.

The Takeaway: Believe in yourself. Granted, I was 18 years into my career and had tried numerous cases before Hayes, many to successful conclusions, but no matter how far along you are, confidence still matters and there are always lessons to learn. Preparation and confidence are the key ingredients to winning jury trials. It is so important that you do not let others shape your view of yourself. Sun Tzu once said, “Pretend inferiority and encourage his arrogance”. My law firm should have T-shirts with that motto. Trial practice is a great barometer for success because you have results that gauge your ability. Even in losses, victories in the presentation of evidence or a favorable ruling on a motion to exclude matters. As young lawyers trying cases the partners wouldn’t touch, we often judged our success by how long we kept the jury out, win or lose. So, appreciate your victories, learn from your failures, remain steadfast and believe in yourself.

Sonnier v. Pittsburgh Corning and PPG Industries (2000)

I started at Provost and Umphrey in Beaumont, Texas in July of 1988. Asbestos litigation was a dominant practice area in the heavily industrialized oil and gas refining industry of Southeast Texas where asbestos insulation had been used in literally every refinery and chemical plant for decades. As a primer, I read Outrageous Misconduct by Paul Brodeur to understand the history. Ironically, the book was dedicated to my father’s former law partner, Ward Stephenson who tried and won the seminal asbestos case Borel v. Fibreboard. Throughout my years at Provost Umphrey, asbestos cases were always a part of my practice and a major source of income for the firm. We had a co-counsel relationship with Ness Motley of Charleston, South Carolina that essentially divided the trial responsibilities between our firms giving them the liability proof and us the causation and medical proof responsibilities.

By the late nineties, many of the asbestos pipe insulation companies had sought Bankruptcy protection except Pittsburgh Corning, PPG Industries and a few others. Pittsburgh Corning (PC) had manufactured a particularly nasty asbestos pipe insulation called Unibestos that contained high quantities of mesothelioma causing amosite asbestos. PPG Industries manufactured a pipe insulation called Pyrocal that was never really a target of lawsuits due to its scant use. PPG also had an ownership stake in PC so getting them on the hook had collateral advantages especially if a bankruptcy occurred.

Sonnier, et. al was a seven-family consolidation of plaintiffs pending before Judge James Mehaffy in Jefferson County, Texas district court. None of the plaintiffs had mesothelioma. They all had varying degrees of asbestosis. One of the clients lived to be 100 years old. Given the makeup of cases, Pittsburgh Corning felt confident they could hold the verdicts down which would influence future settlement negotiations on these and other cases. PC was represented by Bill Harvard from Georgia, an incredible attorney who usually began his side of voir dire by telling the jury, “I’m like Paul Harvey, now you’re going to hear the rest of the story.”

The Ness Motley team was comprised of David Lyle and Ken Wilson, both experienced and excellent trial lawyers and the outstanding paralegal Lane Andrae. If you ever wonder about the value of a great paralegal, ask any NM lawyer about the contribution of Lane to the effort. She knew more about the cases than any of us. I tried our part of the case for the firm.

Our testifying expert pulmonologist was Dr. Gary Friedman. Dr. Friedman was a pioneer in the diagnosis and treatment of asbestos related pulmonary illnesses in Southeast Texas. He was from Beaumont but practiced in nearby Houston. I directed the plaintiffs and Dr. Friedman developing the medical case and handled cross examination of the Defendant’s pulmonology expert. The liability case revolved around some rather ancient depositions Ron Motley and others had taken years ago of PC executives and thought leaders in the medical community including Gerrit Schepers.

In reviewing their expert’s independent medical exams prior to trial, we noticed many of the pulmonary function tests described the height of the plaintiffs above what the other medical records disclosed. Pulmonary Function tests require accurate height measurements in order to assess the volume of the lungs. Because of this, doctors ordinarily measured patients without their shoes on to get an accurate measurement. Many of the experts were not deposed before trial intentionally. We knew what they were going to say from their reports and sometimes with luck, you may expose an area in cross examination they failed to anticipate.

On cross-examination of PC’s pulmonologist, I pointed out that my clients were taller in his reports than in their medical records. I pressed him and obtained his concession that height can affect the calculation of lung volume making their breathing capacity appear less impacted. Surely, he didn’t intend that. There must be an explanation. Sure enough, he testified that his practice varied from that of other doctors. Instead of taking off their shoes, his nurses measured their shoe heels and subtracted the amount. Unfortunately, they failed to include that math in the test results. The jury just stared at him.

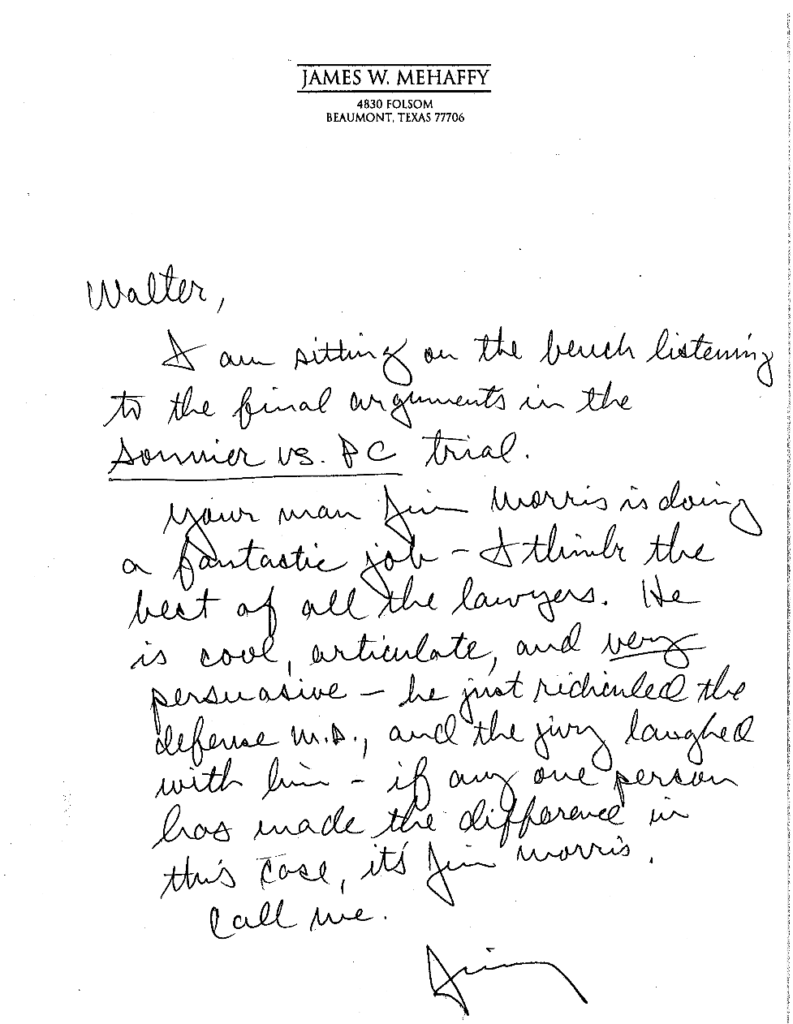

I argued final rebuttal for the plaintiffs, pointing out the incredibility of measuring the client’s heels and pointed out that although my clients were older, the golden years should be golden not winded. We awaited the verdict. The jury returned a unanimous verdict against both defendants for the plaintiffs in the amount of 13 million dollars. The verdict was far beyond what PC anticipated. As a bonus, the jury also found PPG liable for the first time in the history of asbestos litigation. Unfortunately, PC would file bankruptcy within 30 days of the verdict which would delay our client’s payments for almost two decades. Following trial, Judge Mehaffy sent the following note to my boss Walter Umphrey:

The Takeaway: Look for betrayal of trust by the Defendant. Something that appears innocuous may be a window into the soul of the defendant. If they lie or cheat, point it out and tie the conduct to your overall case theme. It is up to you to inform and persuade. Take the craft seriously. Never just mail it in or act like something doesn’t matter. Everything matters. Think about it, the measurement of a plaintiff’s height was likely exaggerated on countless other occasions and never revealed. Here, we called him on it and his response destroyed his and PC’s credibility. Jurors want the truth and straying from it can bury a witness and ruin a case.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) (2004-2010)

Following our success in the Fen-Phen cases, we were contacted by Attorney Mike Williams of Portland, OR and asked to co-counsel HRT cases against our old foe Wyeth involving their drug Prempro. Mike is a mountain of a man with a white beard and affable manner. He graduated from Cal Berkeley and Harvard Law School. He attended Woodstock and was the victim of a near fatal gunshot to the belly as a young man. In the universe of plaintiff’s pharma lawyers, Mike was considered a preeminent mind and trial lawyer. He brought instant credibility to any case. I knew there was much to be learned from Mike.

Prempro was a combination of estrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) used by post-menopausal women to treat symptoms of menopause. By this time, all drug cases seemed to find their way to a Multi-District Litigation (MDL) court due to the volume of cases nationwide. The Judicial Panel on Multi-District Litigation (JPML) appoints one Federal District Judge to oversee the discovery of the cases and to try bellwether cases in an effort to push a global resolution. That Judge appoints a Plaintiff’s Management Committee (PMC) to coordinate and conduct discovery and a liaison counsel to handle communications between the PMC and the many lawyers who suddenly find their cases transferred to the MDL. In order to be on the PMC, you must submit your resume’ to the court and be approved by the Judge. I was approved as a member of the PMC for MDL 1507 by Judge Billy Roy Wilson in Little Rock, AR where the cases would be litigated.

Lead counsel was Zoe Littlepage of Houston, Texas who along with her partner Rainey Booth joined Mike Williams as leaders of what would be a decade long litigation. Zoe was born and raised in Barbados and graduated from Rice University before attending law school. She is an incredible trial lawyer with unparalleled energy and focus on the details. Her skill at cross-examination is the best I’ve ever seen. She dismantled witnesses that the rest of us could barely touch. It was as much art as skill. To call her type A is an understatement. She cannot leave her house with a pillow out of place. What is most endearing is that she knows herself and what you see is what you get.

Rainey, to his credit, was the steady hand in the sea of tumult that surrounded trial preparation. His Hollywood looks and mastery of the details made him the perfect complement to Zoe at trial. Filling out their team was paralegal April Cowgill, who somehow managed Zoe and Rainey while accomplishing more tasks in less time than any paralegal I’ve ever known. Now a breast cancer survivor herself, she is simply a person who makes all around her feel better about themselves.

Other notable members of the PMC included Rob Jenner, Tobi Millrood, Rich Lewis, Jim Szaller, John Restaino, Ralph Cloar, Les Weisbrod, Bill Curtis, Leslie O’Leary, Dianne Fenner and the indominatable Erik Walker. Many others too numerous to name contributed. Wyeth was defended by Williams and Connolly of Washington, D.C., and co-defendant Upjohn was defended by Kaye Scholer of New York, NY. Two large Little Rock firms also defended and acted as local counsel for the drug companies.

Wyeth’s first hormone drug was called Premarin. It consisted of estrogen only. It was developed in the mid-1940’s, about the same time JFK’s sister was suffering a lobotomy. Its FDA approval was grandfathered in the early 1960’s. By the mid-1970’s, Premarin was clearly causing ovarian cancer and the company voluntarily warned about that risk and suggested that a progestin be prescribed in combination for those patients with an intact uterus. The most popular progestin was a drug manufactured by Upjohn called Provera. Provera was generically known as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). So, from the mid-1970’s to the 1990’s, obstetrician-gynecologists prescribed the two drugs in combination for post-menopausal women suffering symptoms including hot flashes, night sweats, and irritability.

Around 1995, the National Institute of Health (NIH), started a nationwide study called the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). The WHI analyzed exposures and conditions in the female population and one of the issues studied was post-menopausal hormone usage and breast cancer. Wyeth had been slow to study this issue and convinced the FDA to allow them to contribute Prempro (the combination of Premarin and Provera) for the study as fulfillment of the Phase 4 study FDA had been requesting from the company.

Studies which follow a cohort of patients who are exposed to a drug have an alarm system in place in case too many adverse events are seen. Breast cancer was the concern with Prempro and sure enough, 5 years into the study, the alarm went off alerting investigators that the cohort had exceeded the acceptable number of breast cancers expected to occur despite the drug. In the subgroup analysis of women who were exposed to Prempro over 10 years, the numbers were truly alarming, in some cases hitting a tripling of the risk. As a result, litigation ensued as women with breast cancer came forward seeking justice.

At the litigation’s core was a failure to adequately study the combination drug and warn the patients of the risk of breast cancer. The first couple of years in the litigation were spent taking depositions, reviewing literally millions of industry documents, and preparing for trial. I was part of the litigation team in the MDL and assisted in depositions as well as individual bellwether case development. Bellwether trials occur routinely in multi-district litigation to give the judge and parties an idea about whether juries will embrace the liability and if so, the value of the cases. Bellwether trials often last weeks if not months and require the participation of several trial lawyers and large staffs.

In 2006, I decided to leave Provost & Umphrey for several reasons. Hurricane Rita devastated Beaumont, Texas in October of 2005 and I was convinced it would happen again. It did, as hurricane’s Ike and Harvey lay testament. Our children, Macy and Trip were just starting school and if ever there was a time to move, now was it.

I agreed to continue to work on Provost Umphrey’s bellwether cases that were approaching trial. We moved to Austin and bought a home in the Lake Travis school district. A couple of months after my relocation, I was contacted by California attorneys Don Edgar and Jeremy Fietz, who had about 200 Prempro cases filed in state court in Philadelphia, PA. Don and Jeremy were familiar with my work in Philly in the Fen-Phen litigation and asked if I would be interested in co-counseling these HRT cases. Given the enormity of the project, I solicited help from former PU partner Brent Coon and we worked out an “of counsel” arrangement that allowed me to accept the cases with Brent’s financing of the project for a cut of the fees.

I established an office in Bee Cave, TX and continued to pursue the litigation. Our children enrolled at Lake Point Elementary and Kam and I got involved in a non-profit theatre academy for kids called TexArts. There, we would meet the incomparable owners Todd and Robin. My cousin Ann Oliverio lived in the nearby community of Lakeway and introduced us to much of the community.

In August of 2006, the Saturday before I was scheduled to drive to Little Rock for the first HRT bellwether trial, I took my five-year-old son Trip, down to the creek behind our house in Austin to clear an area for him to play. I also wanted to educate him on what could be dangerous including a pool of water that harbored water moccasins. As I was raking an area of underbrush near the creek, I was attacked by a swarm of ground wasps. I had no idea that there were wasps that built their nests on the ground, but now I was becoming intimately aware. As they began to sting me, I yelled for Trip to run back to the house. He was only steps away from me and he began running as fast as he could. The house was about a hundred yards away uphill through a grove of mesquite and cedar trees. As I got closer to him, the wasps began stinging him as well and things were not looking good. When I reached the house, I immediately jumped in the pool to hopefully drown the insects. My wife Kam was visiting with dear friends Linda and Larry Sartin and they began attending to Trip.

They called the paramedics given my known allergy to bee stings and help was on the way. The paramedics gave me a regimen of medication and observed me hoping I didn’t go into shock. I had over a hundred stings and Trip had many as well, most on his head. I was primarily stung on my arms and legs. Traveling to Little Rock on Sunday was out, so I would delay my trip for at least a day. I decided to fly rather than drive and scheduled a flight for Monday. Upon arrival in Little Rock, I settled into an apartment we rented for the trial and began preparing Voir Dire. During my first week in Little Rock, I suffered a relapse and recurrence of symptoms causing significant swelling on my arms, legs and chest. I went to the emergency room at St. Vincent’s where I was given a shot and oral medications that boosted my energy and reduced the swelling. The oral medication included hormones ironically. I kept this to myself so as not to alarm my colleagues.

The first bellwether case involved Little Rock resident Linda Reeves. Mrs. Reeves was a breast cancer survivor who had taken Prempro for years and had no idea that the drug could cause breast cancer. At trial, I conducted voir dire and case specific development which included direct examination of her prescribing physician.

The trial team included Zoe Littlepage, Rainey Booth, Mike Williams and me. Zoe focused on liability and Rainey and Mike focused on the science and medical proof. Jury selection went well at least according to the observers that approached me afterwards. We proceeded with the trial. My responsibilities ended after the examination of the prescribing physician and I returned to Austin. Unfortunately, the jury returned with a defense verdict on behalf of Wyeth.

Following my return to Austin, I began working towards trial in Philadelphia since Little Rock wasn’t working out so well. By happenstance, in the spring of 2007, I had the first trial setting of a Prempro case in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas (PCCP). My client Merle Simon had taken Premarin and Provera, so for the first time, both Wyeth and Upjohn would be at trial together as defendants. I was assisted at trial by Brian Ketterer who manned the Philadelphia office of Brent Coon and Associates.

Brian worked with me at Provost Umphrey before moving to BCA, as did Steve Faries. Any success I’ve had in drug litigation is every bit due to the fantastic work of these two gentlemen. I simply can’t over-emphasize the value of case management and briefing on their part. Their work allowed us to avoid summary judgment and provide a defense against these behemoth firms while the tall building lawyers assured their clients that they would annihilate us. Certain people enter your life for good reasons you cannot anticipate. Brian and Steve made a difference.

Wyeth, once again, was defended by Williams and Connolly, this time by partner Heidi Hubbard and Philadelphia Mega Firm Dechert locally. Upjohn was defended by Sidley Austin partner Debra Pole, an energetic defense lawyer of great repute, as well as Kaye Scholer and Hunton and Williams. The trial took place in one of those cavernous courtrooms in Philadelphia City Hall before Judge Alejandro Quinones (Now a federal Judge ED PA). Merle Simon was in her sixties and suffered invasive hormone positive breast cancer requiring surgery. She and her husband Steven lived in New Jersey where they raised two lovely daughters. They were simply excellent clients. I tried the case start to finish for the Simons.

In order to move forward against a manufacturer of drugs, the law in Philadelphia required a showing that the prescribing physician would not have prescribed the drug in light of the newly discovered harm. This opinion by Judge Ackerman set a high burden since most physicians would rarely reverse a prescribing decision. At deposition, Merle’s prescriber testified that the prescribing decision was a cooperative decision between the physician and patient, and if the patient did not want to take the risk, the patient could refuse and the doctor would honor that request. These facts allowed the case to proceed past summary judgment and later were the reason the case was affirmed on appeal.

In opening statement, I reminded the jury of the history of William Penn, whose statue adorns the pinnacle of city hall, in England’s Bushell’s case which established the independence of the jury verdict. I also mentioned Andrew Hamilton and the role of the “Philadelphia Lawyer” in establishing justice through jury trials in colonial times. All of this was an effort to establish the solemnity a citizen’s case deserved against a powerful defendant.

In opening statement, I misspoke when discussing amenorrhea and Debra Pole pounced on me in her opening. Throughout the trial, she made a big deal about the mistake which I owned up to during the case. Never be afraid to own up to your mistakes. Things happen and juries get it. What jurors don’t like is the lawyer who won’t admit a mistake or fallacy. This is true with weaknesses in your evidence. Admit the weaknesses first. Don’t let the other side beat you over the head with it first. Never sacrifice the good for the perfect. Trial is war. Battles over evidence will be won and lost. Keep focused on the ultimate goal. From the outset, let the jury know that they are expected to go back and forth on the evidence, but the credible evidence will favor the plaintiff.

Throughout the development of the HRT litigation, I repeatedly took the position that the easier defendant to hit was Upjohn due to their complete lack of warning regarding breast cancer. Wyeth had, at least, included a minimal statement about the breast cancer epidemiology in their label albeit not the whole story. The case against Wyeth was nuanced by their complicated involvement in women’s health from sponsoring numerous American College of Obstetrician Gynecologist (ACOG) Meetings, ghostwriting articles claiming Prempro had unproven benefits for the heart and mind, and their “dismiss and distract” strategy aimed at refuting negative articles suggesting a breast cancer connection enabled by PR specialists Burson-Marsteller.

Upjohn, on the other hand, just did nothing, which to me, made them the target. The one mention of breast cancer in the Upjohn Label referred to a beagle dog study that found no compelling relationship between the Provera and breast cancer. As I told the jury, we represent women, not canines. The court refused to admit much of the particularly aggravating evidence against Wyeth including the ghostwriting and refused to allow punitive damages. While disappointing, we still had a jury in the box and a verdict on the way. Steve Urbanczyk, a Williams Connolly partner heavily involved in the MDL, sat in the gallery watching the trial and taking notes.

During the trial, the court received a note from a juror directed at me. Apparently, she did not appreciate the fact that I spoke directly to her much of the trial. I am from the school that teaches, “if you don’t look them in the eyes when you deliver your comments, they won’t believe you”. Clearly, there is an exception to every rule, and this was proof. From that point forward, I avoided direct eye contact with her as best I could.

One of the major battles won during Simon concerned the number of diagnosed cases in the large population of patients. Wyeth argued that the number of women with breast cancer was not all that significant, a truly reckless and callous position. Our epidemiologist Don Austin was being cross-examined about the “small” number of breast cancer cases in the exposed population. Without prompting or discussion, Dr. Austin responded on cross with an anecdote to illustrate the significance of small numbers in epidemiology. In April of 2007, 32 students at Virginia Tech were gunned down. Dr. Austin responded, “You know, there are probably 20 Thousand students at Virginia Tech and 32 deaths would be far less than 1%, a “small” number from your point of view. But that number is extremely significant to the ones who lost their lives, to their families and indeed the community as a whole”. The courtroom was deadly quiet and the Wyeth lawyer never recovered from that comment.

Throughout the litigation, Wyeth’s favorite refrain was, “no one knows the cause of breast cancer, not even the experts”. Carrying that banner was a particularly strident Wyeth expert from the University of Pennsylvania named Chodosh. Contrary to his opinion in the courtroom that hormones don’t cause cancer was an admission in one of his patent filings that hormones did in fact cause ovarian cancer. We pointed that out in his cross-examination and successfully encouraged the jurors to examine what the experts say outside of the courtroom versus inside the courtroom.

Ultimately, the jury found in favor of Wyeth but against Upjohn and awarded Mrs. Simon $1.5 million. It was an amazing victory given that this was the first case where Upjohn was a defendant at trial. Wyeth was pleased with their result but had to be concerned that the jury agreed with the plaintiff on the issue of specific cause.

Upjohn appealed Simon first to the intermediate court of appeals where they received no relief and to the Pennsylvania High Court where we also won. Importantly, the appeals courts embraced our position on the learned intermediary issue ruling that a prescribing physician’s acknowledgement that risk, if known, should be discussed with the patient and if the patient rejects the drug due to the risk, her wishes would be accepted. Therefore, the onus on warning lays with the manufacturer to properly warn the doctor so that a collaborative decision can be made.

Often during Simon I thought of Teddy Roosevelt’s quote,

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

If there were one quote for a trial lawyer to live by, this is it. Simon was a watershed moment for me. Dusting yourself off, getting back on and riding that bucking horse is an absolute necessity for a trial lawyer. Wins and losses will occur.

In Little Rock, the fight had not eased a bit. Wyeth was now taking specific characteristics of the plaintiff’s use of the product and arguing that, for instance, short term use (less than five years) would not support a cause-and-effect relationship. The court’s ruling on that motion alone would have a devastating impact on the inventories of plaintiffs and any potential settlement. This, among other issues, were the subject of intense briefing led by Erik Walker, but the question of future bellwethers still lingered.

A few words about Erik. He is brilliant, resilient and without peer. Erik is complex and does not suffer fools. His meticulous expression grammatically coupled with his brilliant insight and analysis was just what Judge Wilson appreciated. Wilson, a rank intellect as well, challenged the lawyers with anecdotes from Hank Williams to the rule in Shelley’s case. Wilson’s respect for Erik worked to our overall benefit. Without Erik, I doubt that the litigation would have succeeded.

In the fall of 2007, I received a call from Zoe regarding MDL bellwether trial settings. She was set to try a three-case state court consolidation in Reno, Nevada during the same period that Judge Wilson had set the third MDL bellwether trial. We were 0 and 2 in the MDL and needed a win. The MDL case involved Little Rock native Donna Scroggin who underwent a double-mastectomy following years of Premarin and Provera use. Ms. Scroggin’s mother was also a breast cancer survivor but not a hormone user. No doubt the primary defense would be the hereditary connection. The good news was that Donna’s BRCA genetic test came back negative for the breast cancer gene.

Zoe asked me if I would take the lead on the Scroggin case. Although Zoe did not say it directly, chances were high I would be “taking one for the team”. I immediately accepted her offer and went to work.

Donna Scroggin was one of those clients who was uncomfortable speaking publicly and had difficulty expressing her emotions. For instance, during trial preparation, we did a mock direct examination. It went like this:

ME: Ms. Scroggin, will you please describe for the jury how you felt when the doctor gave you the breast cancer diagnosis.

Donna: I felt bad.

ME: Can you describe your emotions?

Donna: I was sad.

ME: How did you cope with what you were about to go through?

Donna: I didn’t really do anything, I just had the treatment.

One of the great challenges for trial lawyers is preparing a noncommunicative client to effectively communicate her feelings to the jury. With Donna, it was especially challenging. Explaining the mental impact of a cancer diagnosis gives the jury a clearer picture and allows them a fair assessment to rely upon for awarding damages. I asked Donna to mentally transport herself back in time and describe that cold examination room with bright lights where she sat quietly in her hospital gown as the doctor gravely discussed her diagnosis. I asked her to describe how the tears trickled down her cheeks and began to flow as she coughed and struggled to compose herself. Her first words were, “Am I going to die”. His response was, “Let’s discuss the treatment”…. And so on.

Painting the picture through the client’s images and pictures drawn from their memory is crucial to establishing the emotional congruence that gives the jury an opportunity to share the grief, despair and loneliness that goes with the diagnosis. The same is true for the fear, anxiety and uncertainty that goes with the treatment. It’s not enough to just say it turned my world upside down. The client must state how it did so. For instance, Donna normally visited her elderly mother every day, but now that was put on hold. How many more days, months or years did her mom have, or Donna have for that matter? She worried about this. She normally was in charge of a local club, but now someone else would have to take over. Historically, she did not deal well with pain. Now she had to endure having both of breasts amputated. Painting those pictures is not pandering for sympathy, it is an expression of truth.

Trial took place in the late winter of 2008. Since it was an MDL trial, the committee provided April Cowgill to provide support to Terry Nash and Erik Walker to handle all motion related legal issues. Steve Faries handled the case management and I tried the case from Voir Dire to final argument on my own. I handled every examination and argument during the five-week trial.

Wyeth was defended by Williams Connolly partners Lane Heard and Steve Urbanczyk, Arnold and Porter lawyer Pam Yates, and locally by Lyn Pruitt. Upjohn called on Baltimore lawyer Charlie Goodell and local lawyer Betsy Murray. Behind them were a cadre of associates, paralegals and support staff. Many federal judges listen more carefully to the defense side of motions because of the age-old bias that assumes that the smartest lawyers go to the large defense firms. A perception but not the truth. Granted, Lane Heard was a Harvard graduate and Urbanczyk from Stanford, but neither could match Erik Walker and thank goodness Judge Wilson listened to Erik.

Counseling me during voir dire was rock solid, Southern Baptist, pillar of the community, Little Rock native Ralph Cloar. Ralph’s wife was a breast cancer survivor and he knew the judge and community very well. We didn’t utilize a jury consultant or overthink which prospective jurors would be best. One prospective juror’s sister suffered breast cancer but never took hormones. We were concerned that she might buy into the argument that “no one knows the cause of breast cancer” given her sister’s diagnosis. So, we struck her and instead took a lumber company safety foreman who answered the jury questionnaire section asking about the three person’s you admire most by putting 1. My dad 2. Jesus Christ and 3. George Bush. The three people he admired least were 1. Hillary Clinton 2. Bill Clinton and 3. Richard Simmons. He was our jury foreman. The judge seated twelve jurors and two alternates and off we went.

Trial proceeded as predicted. It was bifurcated between actual damages and punitive damages, so we would not be able to present the really damaging gross negligence evidence unless we won the first phase. The plaintiff testified as did our numerous expert witnesses. Much of the scientific evidence was like Simon. Our FDA expert Suzanne Parisian explained the role of the FDA telling the jurors that the FDA doesn’t actually test drugs. The manufacturers do the testing and send the results to the FDA which reviews them for accuracy. So, the fox is guarding the hen house. She also explained that FDA has on only one occasion involuntarily withdrawn a drug from the market. Clearly, the drug companies control much of what happens and despite the best efforts of the regulators, bad drugs make it to the market.

Wyeth relied heavily on its Johns Hopkins trained Genetics expert who presented a family tree suggesting that this breast cancer, in fact, was caused by genetics and not the drug. I was able to pick apart the tree and show that the only hereditary link Donna had was her mother and yet Donna did not possess the BRCA gene which would cement the connection. The preponderance of the evidence, given Donna’s long-term usage pointed to the drug not genetics, I would later argue.

Throughout the trial, Judge Wilson referred to me, outside of the presence of the jury, as Reverend Morris and seemed to take sport with my delivery. The Wyeth lawyers were tolerable and Goodell was actually likeable. Urbanczyk backhandedly complemented me one day saying, “You’ve improved since Simon.” One of the more colorful moments occurred at sidebar one day when Judge Wilson complemented my grey pin striped suit by saying, “I doubt I’ll ever buy another suit, but if I do, I want one like that.” Lane Heard, an extremely dapper dresser, was green with envy.

At the conclusion of the plaintiff’s evidence, I approached Goodell and took him aside. I told him that my client was a very reasonable person and she would be willing to negotiate a settlement. After all, the judge had denied their motion for a directed verdict against us which meant the case would get to the jury eventually. Charlie was candid and said that he had been instructed to offer nothing.

Trial ended and the jury retired to deliberate. We all expected that the process would take a while and the court promised to call us when the jury returned. Late that day, the bell rang and the jury had reached a verdict. April was walking up the courthouse stairs next to the defense attorneys who all seemed to be rather excited. She asked one of the lawyers why they were so cheerful, and he responded, “we’ve got it in the bag”.

Kam came to Little Rock to attend final argument and be there as moral support for the verdict. Honestly, we had no idea how things would go. Juries are never predictable and our trial track record in Little Rock was abysmal. Bifurcation always makes getting a verdict more difficult. Many jurors want more than a preponderance of the evidence to find against a defendant. Evidence of conscious indifference, only allowed in the punitive phase, could assist some wary jurors during the actual damage phase.We reached the courtroom and took our seats as the jury filed into the box. The Foreman passed the verdict to the court’s clerk, who read the verdict to the packed courtroom. The unanimous Jury finds in favor of the plaintiff Donna Scroggin and against both defendants and awards 2.7 million dollars. I just dropped my head as Steve patted me on the back. I reached over and held Donna’s hand for a moment as the Judge addressed the courtroom and polled the jury. They all agreed that the verdict was theirs and the court asked them to remain seated.

The Judge then looked to me and said, “Mr. Morris, are you prepared to begin the punitive damage evidence.” Caught somewhat aback, and still reeling from the shock of the win, I murmured, “Yes we are your honor”. Predictably, the entire defense side of the courtroom objected in unison as they quickly began to realize the train that had just slammed into their cars. In response, the court called the lawyers to sidebar and we began discussing the future. The defense needed time to digest the jury verdict and assemble their evidence and witnesses and yada, yada, yada. I, on the other hand was ready to proceed. The jury needed to see the good evidence that the public had not yet seen.

Wilson was a trial lawyer before becoming a judge. He embraced the jury trial as a necessary part of reaching the truth. He refused to engage in settlement discussions throughout the litigation and simply let the cards fall where they did. He gave us two days to prepare for the next phase and instructed the jury to return at that time.

Proceeding to the punitive phase was complicated. Much of the punitive damage evidence came from the Wyeth marketing and medical affairs departments. The Wyeth evidence included ghostwritten articles dismissing the breast cancer risk and distracting the reader to believe that Prempro was beneficial for the heart and mind even though the FDA had never approved those alleged benefits. Since it would be illegal for the manufacturer itself to make those unfounded claims, Wyeth worked through ACOG and other thought leaders to spread the untruthful messages. Wyeth’s campaign of disinformation found its way into direct-to-consumer ads and genuinely persuaded medical doctors to underestimate the risks and overestimate the benefits, a truly terrible thing for patients.

Although the documentary evidence should have come in on its own merit, Wilson, like many judges, required a sponsoring witness. Most of this evidence included things the FDA should have known but didn’t. As such, we used Dr. Parisian, our FDA expert, to sponsor many of the exhibits. The jury listened carefully, sometimes with their mouths wide open, as the truth of pharmaceutical marketing in America came to light. We presented the evidence over a couple of days and then made our final arguments.

The U.S. Supreme Court has on numerous occasions been confronted with the constitutionality of punitive damages. Most trial lawyers are familiar with the high court’s BMW decision that found a verdict with a ratio of 1:8 between actual and punitive damages to be acceptable. As such, I argued for a 1:10 ratio assuming the jury might cut it in half. Wyeth and Upjohn both denied any punitive award was warranted but from their facial expressions, it didn’t look to me like the jury was buying it. The jury retired to deliberate and returned after several hours. They, once again, passed their verdict to the court’s clerk who read the following: “The jury finds in favor of the Plaintiff on the issue of punitive damages and assesses $19,366,000.00 against Wyeth and $7,760,000.00 against Upjohn.” After all was said and done, the jury assessed exactly the ratio I suggested.

The Defendants were stunned. Walking out of the courthouse, I saw one of the defense lawyers who had given up smoking years ago, sucking down a Marlboro in complete disbelief of what had just happened.

As with any significant verdict, both Wyeth and Upjohn moved for a new trial and to set aside portions of the verdict, primarily the punitive damages. Roughly thirty days later, we received the court’s decisions. Judge Wilson denied their motions for new trial but entered a judgment notwithstanding the verdict (jnov) that set aside our entire punitive damages award, all 27 million dollars. Gone, poof, goodbye. In his lengthy opinion, he stated that he was mistaken in admitting all the damning documents testified to by Dr. Parisian who he should not have let testify. Fortunately, he upheld the actual damage award which the defendants appealed to the 8th circuit. We appealed his jnov of the punitive damages and Erik went to work on the appeal.

The 8th Circuit in a published opinion affirmed our actual damage verdict. They reversed his decision on the punitive damages but rather than reinstating the 27 million, remanded that portion for a new trial. The defendants appealed the 8th Circuit’s decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court refused to upset the 8th Circuit’s decision and the case resolved in our favor.

My trial calendar for 2009 included 5 trials in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas. Given that each case would take at least a month to try and Wyeth seemed hell bent to keep up the fight, I needed to consider my situation. I was way too deep to back off the litigation, but I didn’t want to spend a year away from my family. Our daughter Macy was 10 and our son Trip was 8 and being around was really important for all of us. What if we moved to Philadelphia temporarily?

I explained the situation to Kam in December of 2008 and she agreed that moving made the most sense. We spoke to friends who recommended the Philadelphia Main Line as a great place for schools and quality of life and off we went. We moved close to Narberth and put our children in school at Belmont Hills Elementary. I put my office across from City Hall with friend and colleague Diane Fenner, who lived in nearby Bryn Mawr. We learned how to pronounce Conshohocken and Schuylkill.

Moving and living among the community enhanced my awareness at trial. I learned how to pronounce local places and understood a little bit of the personalities of the different neighborhoods. Don’t get me wrong, it’s nothing like being from there, but the awareness and understanding of things local helped. Being able to sleep at home rather than in a hotel helped. Putting Trip in the Hilltop Little League and playing golf at Bala are experiences I will never forget. We made friends in Philadelphia that are part of the fabric of our lives.

Over the next 8 months, I tried 2 more HRT trials in Philadelphia and settled one on the courthouse steps. Wyeth brought in Beth Wilkinson as its lead trial lawyer for two of the cases. Beth is married to David Gregory, formerly of Meet the Press and she is formidable. Her manner is convincing and she is similar to Zoe in terms of focus. In fact, my final HRT trial in February of 2010 was a 2-case consolidation I tried with Zoe and Rainey in Judge Jimmy Lynn’s court. Beth tried that case for Wyeth and won. Our client was a wonderful lady named Sharon Buxton who, despite our loss, is still my friend on Facebook. It was shortly after that loss that I settled our HRT inventory and returned our family to Texas.

Scroggin ended up being the only plaintiff’s verdict in the Federal MDL Court. The cases settled globally in 2010 after numerous huge state court verdicts recorded by Zoe, Tobi and others. Pfizer bought Wyeth and Prempro remains on the market. I was lucky to be a part of the litigation and I sincerely doubt that any legal experience will ever match the Prempro litigation.

THE TAKEAWAY: Never Quit. Believe in yourself. Persevere. Take chances.

Ophelia Mouton v. Howard’s Food Market (1987)

My first solo civil trial was a slip and fall case on behalf of Ophelia Mouton against Howard’s Food Market. My boss gave me the file the Friday before jury selection on Monday. The file had little information other than some chiropractic bills and a denial of liability letter by Howard’s. There was also a smattering of discovery requests that had either been objected to or left blank. The defense lawyer was several years ahead of me and knew what he was doing.

Ophelia showed up for court in her “Sunday best” with an inordinate amount of makeup. Her key witness was Kizzie who lived at Ophelia’s house along with several other barely legal girls. The case was tried in Jefferson County Court at Law #1, a court of limited jurisdiction that utilized a six-person jury. We picked the jury, gave opening statements and began the presentation of our case. Ophelia took the stand and explained how she was walking through the produce section with Kizzie on a routine shopping trip and slipped on a mess the good folks at Howard’s had failed to clean up. This occurred in the mid-1980’s so no one had a cell phone to snap a photo of the condition of the premises. Howard’s denied responsibility claiming there was no notice of the condition and denied failing to remedy the premise defect.

I tagged all the bases in direct examination of Ophelia by describing her activities that day, the fall, her report of the fall and the pain and suffering she endured following the incident. Ophelia was cross-examined about her deposition testimony. At deposition, she testified to never having any previous lawsuits. On cross, Ophelia confirmed that she had not previously sued anyone and was adamant about the fact. The nice defense attorney then approached Ophelia with a stack of papers in his hand that I had not seen. Of course, I objected, and he responded by arguing that these were being used for impeachment purposes. At sidebar, he argued that I had equal access to the documents had I taken the time to order copies of his subpoenaed documents. I’m thinking, how could I do that between Friday and Monday. The Judge overruled my objection and allowed defense counsel to proceed. He showed Ophelia not one but 6 previous lawsuits she had filed, 5 of which were slip and falls. The jury was stone-faced. I did my best not to react.

Despite the impeachment, Kizzie backed up Ophelia’s story concerning the produce aisle defects and how Ophelia continues to suffer with pain as a result of the incident. In final argument, I argued that her prior lawsuits had nothing to do with this incident and that Kizzie was a credible eyewitness to the fall. I then argued for a modest amount of 15 thousand dollars and took my seat. Ophelia grabbed my arm as I sat down and in earshot of the jury said, “your boss told me this case was worth 50 thousand dollars.” I whispered back to her, “I don’t think the amount is going to be the problem”. As anticipated, the jury found in favor of Howard’s and I notched my first civil loss.

Busy personal injury practices are full of their share of Ophelia’s and while this case played out in less than stellar fashion, many of the problems were avoidable. Small PI cases with no surgery, slim medical visits and tough liability are historically the training ground for young lawyers. While the public might be offended that Ophelia got her day in court, there are many Ophelia’s that don’t, thanks to summary judgment, or simply no lawyer willing to take the case. The benefit of allowing Ophelia her day in court is the prospect that while the testimony seemed crystal clear, given slightly different facts, the case may have gone her way.

For instance, imagine that the chiropractor actually asked for a CAT scan because Ophelia claimed her head hit the ground. Imagine that the CAT scan showed a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) that affected her memory. Imagine that this was unknown at the time of her deposition and she failed to remember the earlier incidents just as she may have for gotten previous husbands, residences and occupations. All of the sudden, the impeachment looks cruel.

Imagine that Ophelia showed up to court wearing normal clothes and no makeup. Imagine that Kizzie was a homeless child Ophelia had befriended and taken in when no one else would. Imagine that Howard’s had a habit of not documenting routine cleaning and had 15 prior reports in just that year. All of the sudden, the verdict could go Ophelia’s way and in a big fashion.

THE TAKEAWAY: First, I learned that facts are stubborn things. The discovery in our file did not include any information that would rebut her lack of memory at deposition. Neither Ophelia nor her witness had any proof in terms of physical evidence to support the claim. The medical records in Ophelia’s case consisted of a few chiropractic adjustments, but no diagnostic tests showing anything. Finally, neither Ophelia nor Kizzie were particularly believable.

THE TAKEAWAY: The case allowed me to stand on my feet and pick a jury. Nothing is more valuable than just doing it. You can read books and attend seminars and watch other people examine a panel, but nothing is more instructive than just doing it on your own. Jurors want to be fair. They lean towards the truth and take their job seriously. They are not stupid. They know that young lawyers often get the worst cases and oftentimes they empathize with your plight. While some may walk away griping about how you wasted their time, most walk away satisfied that they performed a public service that is a privilege in a free society.

Additionally, you must know what the other side has in their file. From that day forward, I wanted every statement my client spoke, wrote or pled that the defense possessed for direct and impeachment purposes. I want every investigative report, every background check, criminal or otherwise, every employment record, medical record and relevant company record relating to the case and its witnesses. Finally, I learned that I needed more lead time. Years ago, a “seat of the pants, throw it on the wall” approach was not uncommon especially if the litigation costs were to be kept in check. Today, the internet allows case construction at a much-abbreviated cost. Bottom line, do the discovery homework, anticipate the defense, and be prepared.

Randy Stafford v. Keller Industries (1988)

Randy Stafford was fired from his job following a worker’s compensation claim. He was a long-term employee without significant personnel complaints. In fact, the thing that made his case palatable was that the employer did not give a reason for his termination. The temporal relationship between his filing of the worker’s compensation claim and his termination were close, so circumstantial evidence suggested that the termination was related to his filing of a claim.

Randy was not litigious. He had no prior lawsuits or criminal convictions. He was a reliable employee and very credible on all issues. We tried the case in two days and after two hours of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict in Randy’s favor and awarded a sum that covered the time he was unemployed. The Defendant appealed the case to the 9th Court of Appeals where we won and to the Texas Supreme Court where we also won.

THE TAKEAWAY: Most plaintiff’s cases rise and fall on the credibility of the plaintiff. Having a deserving plaintiff who merely wants what is fair goes a long way with jurors. Jurors are often suspicious of a plaintiff who appears too slick or seems to have a motive to game the system.

Every trial lawyer develops certain repetitive strategies that resonate with a jury. There are countless books that discuss issue framing and things like the Reptile approach. These books should be read and utilized. There are also seminars that instruct on rhetorical tools and the appropriate manner, eye contact and physical presence that works with juries. My favorite is Trojan Horse Method with Dan Ambrose. Gerry Spence’s Trial Lawyer’s College is also excellent. At a minimum, every trial lawyer should conduct mock arguments in front of a mirror and in front of critics. How the tone of your voice rises and falls matters. The volume of your voice matters. The pace at which you deliver your speech matters. What you do with your hands matters. How you make eye contact and for how long to each listener matters. Your posture and movement in the courtroom matters. Courtrooms are the stage and every movement and word matters to the jury. Finally, the substance also matters, so do your homework and be prepared on every detail.

One of the approaches I used in Stafford and still use to this day is making commitments to certain proof in opening statement and checking those commitments off in closing statement. “I promised you that the evidence would show that Randy did not violate any company policy. Here we are in closing argument and the defense failed to prove one instance of a violation. Promise made, promise kept.” Being able to make and keep promises is important to everyone. Trials are about presentation, proof and promises. Although this seems terribly elementary, bookending your proof with promises made and promises kept gives jurors a reason to see it your way and specific evidence to persuade other jurors that are not going your way.

Keith Van Boskirk v. Texas A & M (1991)

Keith Van Boskirk was a student at Texas A & M University. He participated in the annual building of the bonfire performed solely by students at the time. The Texas A&M bonfire was the largest bonfire on any college campus. The students, often referred to as Red Pots and Brown Pots, cut down full size pine trees, stacked them vertically, doused them with propellant and set them ablaze historically the night before the annual football game against the University of Texas Longhorns. Keith was involved in the harvesting of the trees. Unfortunately, one of those trees fell the wrong way and collided with Keith fracturing his pelvis.

I sued A&M contending that they failed to properly supervise the bonfire preparation process. In Texas, Universities are generally immune from suit unless you can prove that a condition or use of real or personal property by the university caused the injury. We contended that the use of the trees was indeed covered by the tort claims exception and the court agreed allowing us to try the case.

I tried in the case in College Station, the home of Texas A&M. Voir dire was particularly challenging given the partisan panels who simply loved A&M and the bonfire. Many of the venirepersons worked for the University or had some affiliation as a former student, parent, or vendor. Fielding an unbiased jury was practically impossible. We were unable to move the case to a different County, so I was stuck with a panel that despite my efforts still had Aggie lovers. I tried the case twice to 2 different hung juries. In final argument, I warned the jury that one day a real tragedy would occur given the enormity of the project and the lack of substantial supervision. On that, I was unfortunately prophetic.

After the second hung jury (9-3 in my favor), Texas A&M renewed their earlier Motion for Summary Judgment and the court granted it dismissing our case. Following the summary judgment order, I instructed my paralegal to file a notice of appeal which she promptly did. I failed to instruct her to file an appeal bond, which, at the time was jurisdictional. Thirty days later I received an Order dismissing the Appeal for failing to file a cost bond. I immediately realized I had likely committed malpractice, although there was no certainty any jury would find the case could succeed after 2 juries could not agree. My boss, after chastising me for the inexcusable oversight, took the practical approach and had me call in the client, explain my mistake and its implications and see if we could pay something in compensation to avoid a lawsuit. Fortunately, the client was completely reasonable, and we were able to resolve the circumstance amicably.

Six months later, I was reviewing the advance sheets as we did before the internet, and I ran across a case from the Texas Supreme Court involving a lawyer who, like me, had filed a notice of appeal but failed to file an appeal bond. Rather than accepting the long standing but unfair rule, he appealed his case to the Texas Supreme Court arguing notice was what mattered more than the ministerial payment of the bond. The High Court reversed the long-standing rule that the bond was jurisdictional and reinstated his appeal.

THE TAKEAWAY: Always read and re-read procedural and local rules before you engage in any legal endeavor that is not part of your routine practice. Do not delegate matters of that importance to a non-lawyer. Finally, if something seems manifestly unfair, challenge it. Obviously, I wished that I had appealed the decision of the court of appeals to dismiss our appeal as the lawyer in the later case had. Had I done that, I would have been able to continue my appeal of the summary judgment and at least had a chance at a third trial. The other major takeaway is the reaction of my boss. Lawyers make mistakes. Having the maturity to not overreact is amazing in retrospect. I probably would have fired me. Don’t get me wrong, this event set me back reputation wise and probably delayed my partnership track for years, but he didn’t give up on me. I never made that mistake again.

William Guillory v. TEIA (1991)

My father was a trial lawyer. He was the District Attorney in Orange County, Texas when I was born in 1961. Later, he was a criminal defense lawyer and won more than his share of acquittals. Following my freshman year in college, my father felt that I should understand the importance of making good grades, so he contacted the local Boilermakers Union boss, Dewey P. Cox, and arranged for me to apprentice during the summer at the local refineries. I was assigned to Bill Guillory, who was a Superintendent. Over the summer of 1980, I worked in vessels, towers and tanks mainly cleaning up after the boilermakers who performed maintenance on the equipment.

Ten years later, Bill Guillory came to our firm following an on-the-job injury. His case was assigned to me at his request. The case was a fairly routine worker’s compensation industrial injury case and the Insurance company simply did not want to compensate Bill. The file had several sets of medical records and bills. In those days, everything was printed and much of the organization was left up to the lawyer. Bill had a son named Bill who also used the same doctor as his father. During the course of discovery, young Bills records were interspersed with his father’s and of course there were factual inconsistencies that made the records distinguishable.

During trial, I submitted into evidence a large stack of medical records that inadvertently included a record that was young Bills. At a break, I noticed my mistake and simply substituted the correct record with the wrong one. The problem was I failed to ask leave of court to do so. The court reporter saw what I did and reported it to the Judge and opposing counsel. The Judge called us into chambers and berated me for tampering with the evidence. He offered to give the opposing counsel a mistrial which he declined and forced me to call my boss in his presence and explain my conduct. We did just that and I explained that my intent was to provide a clear record and I did not intend to break any rules. Nevertheless, I was I big trouble. The court refused to allow me to correct the record and we proceeded with trial.

Defense counsel used the son’s records to prove that no diagnosis of a back injury existed and my client must be lying. I couldn’t believe that he was using the records in that manner. I objected, but the court still fuming at my conduct over-ruled my objection and let the farce continue. On re-direct, I pointed out the difference in dates of birth and asked my client if he was indeed 24 years of age to which he said no and I asked him if he had a son of the same name who was also treated by the doctor and he said Yes. The points were made.

In final argument, defense counsel continued to pursue the wrong records as proof of my client’s lack of injury, even though the jury now understood the mistake. In my closing argument, I fell on my sword and told the jury I made an inexcusable mistake. I then asked them not to punish my client for my conduct and asked them to consider the real evidence. Throughout the entire ordeal, my client kept asking me, “What’s the big deal?” Worried about the outcome, I demurred and promised we would discuss it after the verdict. The jury returned a verdict in favor of my client and awarded the maximum amount allowable under the law. Afterwards, the jury told me that the truth mattered more than my mistake and that they were upset with how the defense lawyer misused the records. Thankfully, the Defendant paid the judgment in full without appeal.

THE TAKEAWAY: Mistakes happen in trial and most are curable. As a young lawyer, if a mistake occurs, think carefully about seeking the court’s guidance or that of a colleague before you proceed. The devil is in the details. Oftentimes we are overwhelmed by the paper. During those early years, I conducted trials without co-counsel or any trial support whatsoever. I marked my own exhibits, introduced them, handled all motion practice and all the administrative tasks that accompany a trial. Many lawyers still do, and it is no easy task. I now conduct trials with every document in folders in a notebook, so that I don’t get anything mixed up. Much of the time, we organize everything electronically and try cases paperless. It’s simple but effective. Organization should begin the day the case comes in. There should be separate files for plaintiff and defendant’s pleadings, discovery, document production, evidence, motions, orders, contact with client, correspondence, expenses, depositions, research, insurance, photographs, videos, experts, medical records, medical bills, wage loss, and anything else relevant to your specific case. It is critical to be organized in front of a jury. The jury forgave me on this occasion, but don’t press your luck.

CIMINO v. RAYMARK INDUSTRIES (1990)

In 1989 and 1990, Provost and Umphrey along with Ness Motley and Reaud, Morgan and Quinn pursued a 2298 plaintiff asbestos class action/consolidation against Fibreboard, Pittsburgh Corning, Armstrong Contracting and Supply and Carey Corporation. The USDC Easter District of Texas had accumulated thousands of asbestos cases over the preceding years and a class action trial seemed like the best way to dispose of the backlog. At this point, multi-district litigation had not taken over the coordination and discovery of mass torts. Judge Robert Parker devised a procedure that would include three phases of the overall litigation. Judge Parker would oversee the first phase which involved 10 class representatives on the issues of liability and gross negligence. The second phase would be a product identification phase that would theoretically assign percentages of exposure by product to the class members. How that would be tried was not entirely clear and ultimately the parties entered into a stipulation that assigned agreed upon values to each defendant. The third phase consisted of 160 sample cases of varying degrees of illness which would be tried as essentially damage trials whose verdicts would be extrapolated to the entire class, a novel theory. Trial of the sample cases were divided between Senior Judge Joe Fisher and Judge Richard Schell. Internally, Greg Thompson led a team in Judge Fisher’s court and Diane Dwight led a team in Judge Schell’s court. Most of the sample cases were tried by associate attorneys at Provost & Umphrey and Reaud, Morgan and Quinn. I tried 18 of those cases, all before Judge Fisher.

All told, each side of the litigation utilized fifty or more lawyers in the three-phase trial. All phases were tried over a nine-month period. At the helm in Phase one for the plaintiffs were Walter Umphrey, my boss, and Ron Motley, a legendary asbestos trial lawyer and Wayne Reaud. The Defendants were led by Bob Daggett, Henry Garrard and Bill Harvard among others. Also taking the lead for the plaintiffs were Glen Morgan, Chris Quinn, Joe Rice, Greg Thompson, Diane Dwight, Chip Ferguson, Brent Coon, and David Brandom. Many others participated.